Wherever Carl Eifler went, sound and fury followed.

The so-called “deadliest colonel” has a near mythical reputation among historians. On paper, there was no mission too crazy or too dangerous for him to accept.

He even embarked on some of these missions.

But most he did not.

This article will build on another I wrote back in January, which I believe is one of the most important articles I have published to date. I highly suggest reading (or re-reading) that article before continuing with this one.

What was Project NAPKO?

Carl Eifler, a big and burly covert operator during World War II, suffered a traumatic brain injury when his head crashed into rocks just off the coast during a mission in Asia midway through the war.

After the injury, his behavior became erratic, evoking a famous scene from the film Apocalypse Now.

A 2019 article in World War II magazine by Nicholas Reynolds describes in detail the delicate manner in which the OSS handled this issue (emphasis added).

As [OSS leader William] Donovan told [Army General Joseph] Stilwell, he had decided that Eifler would be going to Washington for a “brief refresher course in our work”—a face-saving way of saying that Eifler was being relieved of command…

Donovan soon softened the blow by making Eifler a special projects officer, eventually giving him the title of commander of the Field Experimental Unit (FEU)—charged with exploring missions impossible out of OSS Headquarters…

[For] Project NAPKO…the FEU would run paramilitary operations in Korea—a country that had been a de facto Japanese colony since 1910 and was, like Japan itself, largely a closed book to American planners even after more than three years of war. In a comprehensive memorandum that he would forward to Donovan on March 7, 1945, Eifler laid out the many details he and his men had considered. He began with an ambitious, even grandiose, statement of purpose that envisioned the possibility of revolution growing from this small-scale operation.

NAPKO, which may have stood for “Naval Penetration of Korea”, was to involve landing small groups of Korean agents in miniature submersibles at various points along the Korean and/or Japanese coast.

An article in the CIA’s in-house publication, Studies in Intelligence, goes into great depth about the submersibles, including their specs.

Agents were selected from a group of Korean POWs and shipped off to Santa Catalina Island, off the coast of California, for training in the spring and summer of 1945.

Reynolds writes, “The OSS had begun leasing parcels there in late 1943; Eifler’s FEU occupied two isolated locations and a boat ramp.” (emphasis added)

As noted previously, there was a third location on the island where, supposedly, Koreans were being trained. This site was completely separate from the other two.

The war ended before Project NAPKO could be fully operationalized, and Carl Eifler returned to civilian life.

Eifler continued to struggle with seizures and memory loss, enduring long periods of hospitalization in 1945 and 1946. Perhaps to atone for wartime guilt (he commented more than once that members of Det[achment] 101 [the group he led in the CBI theater] had committed war crimes), he eventually received degrees in divinity and psychology from Jackson College, a small missionary school in Hawaii. In the 1950s Eifler went on to earn a PhD in clinical psychology at Chicago’s Illinois Institute of Technology, and then worked for the Department of Health in Monterey County, California, where he developed a reputation for compassion and engagement. He died in April 2002 at the age of 95.

Connecting the dots

Five topics have been floating around in my head for months, and I have tried to figure out how they fit together:

Carl Eifler

Santa Catalina Island

Maritime operations

Special Projects

Nassau, the Bahamas

Project NAPKO is the link.

Carl Eifler was in charge of the operation, the agents for which were trained on Catalina Island. NAPKO was a maritime, or sea-landing, operation. When Eifler was relieved of his command in the CBI theater, Bill Donovan made him a Special Projects officer. The OSS had a Maritime Unit, and the two major training locations for this branch were Catalina Island and Nassau.

Who is connected to all five of these keywords?

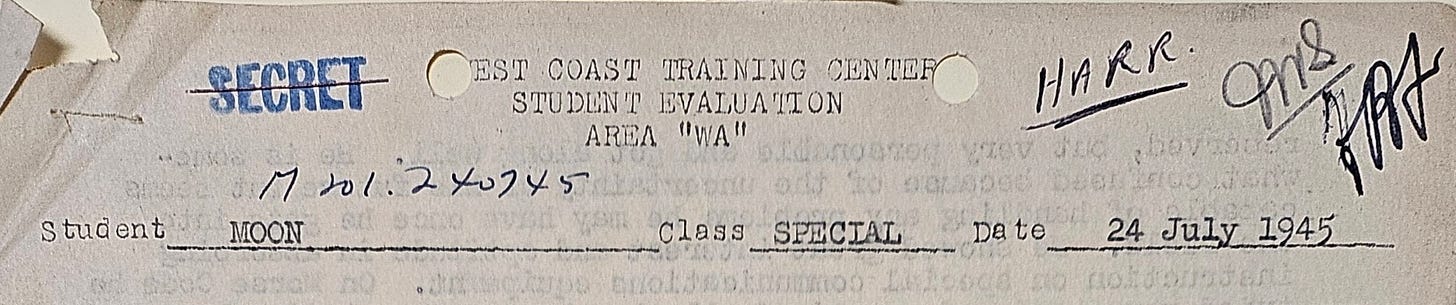

The OSS agent Moon Duck Harr.

I believe this fictitious name is a stand-in for Karl G. Harr Jr., Jay’s cousin, who would go on to serve as a special assistant to President Eisenhower in the late 1950s.

Moon Duck Harr’s student evaluation from July 24, 1945, lists his class as “Special”. Originally, I thought that referred to Special Operations, a branch of the OSS. However, as I reviewed more and more documents from this branch, I noticed it was consistently abbreviated as SO, not Special.

When I learned about the Special Projects branch, that immediately became my leading hypothesis. The fact that Carl Eifler, a Special Operations officer, was in charge of training Koreans on Catalina Island for Project NAPKO is further evidence supporting the assertion that Moon Duck Harr was being trained for a Special Operations mission.

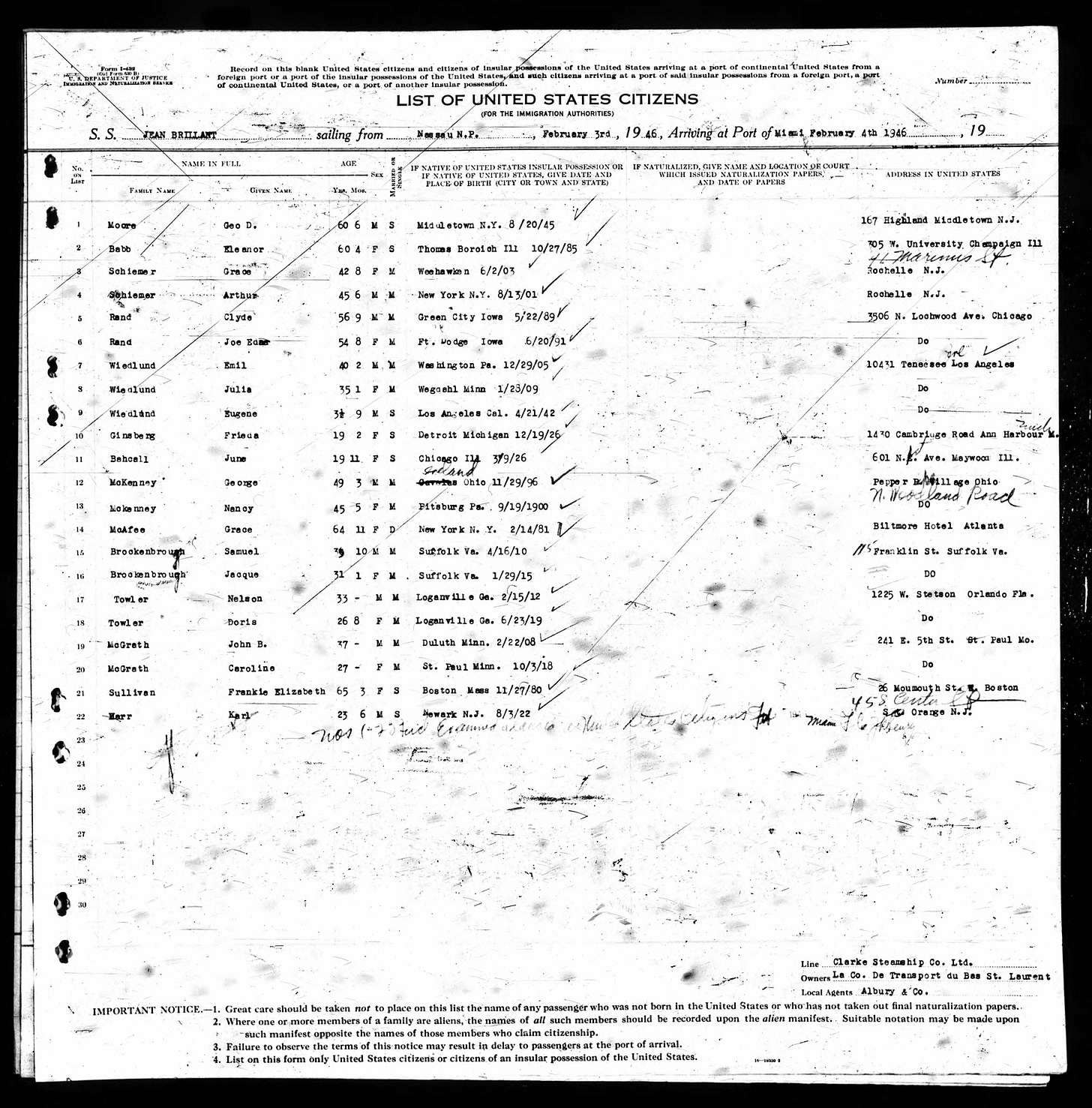

The final piece of this puzzle - Nassau, the Bahamas - comes not from an OSS document, but rather from Karl Harr’s travel records.

On February 3, 1946, Karl Harr returned to the United States from Nassau aboard the M.V. Jean Brillant, a ship built in England in 1935 and owned by the Clark Steamship Company.

Whatever brought Karl to Nassau must have been pretty important. It appears he was given as much time as possible to recuperate from the airplane crash the previous November.

Exactly one week after his return, Karl was discharged from the Army.