Two weeks ago, I wrote about the formation of the President’s Committee on Information Activities Abroad, commonly referred to as the Sprague Committee.

Last week, I covered the introduction and first two chapters of the report.

Today, I will examine the remaining portions of the report.

Although I stopped after chapter two last week, I will pick up today in chapter four. Chapter 3, which discusses student exchanges, English language teaching initiatives, and higher education outreach, is not germane to my research.

Psychological and informational dynamics of economic aid

The report clearly states that the scope of the Committee’s recommendations on economic aid is restricted to that which is directly provided to another country by the United States.

There is no mention of third party intermediaries, such as international organizations like the International Monetary Fund.

However, because the United States has, since the beginning, controlled by far the largest voting share of the IMF’s Executive Committee, it is safe to say that anything the U.S. delegation voted for during this era should have been aligned with the findings in the report.

In addition, although I do not have evidence from individual votes, logic and math dictate that few IMF votes on major policy prescriptions are passed over the objections of the United States.

It is with this understanding that I took note of the purpose of economic aid, as detailed by the Committee (emphasis in all cases is added):

The importance of changing basic institutions and attitudes derives not only from the necessities for economic growth, but from the overriding political objectives toward which all our foreign programs, economic and other, must be directed.

Put differently, one reason the U.S. provides international aid is to change a country’s political institutions to better align with American interests.

Importantly, the report advises policymakers to be measured when evaluating American economic aid programs:

In brief, we must see clearly the role of our aid program in the larger context of the overall objectives of U.S. foreign policy. But we must see equally clearly those psychological objectives which are really worth pursuing in advancing development and political relationships, and those which are merely gratifying to our self-pride.

Here, the Committee clearly sees the potential for future leaders to overuse this particular tool of foreign policy.

New dimensions of diplomacy

The Committee’s report was published just as the U.S. intelligence apparatus was pivoting away from direct confrontation with the Soviet Union in favor of proxy battles in the so-called nonaligned countries.

In these countries, the Committee stresses the importance of communication, focusing specifically on the state department. Again, a warning is conveyed about taking things too far:

The Committee recognizes, first, that the Department [of State], with its responsibilities for the conduct of foreign relations, must exercise extraordinary care and fidelity in its methods and approach. It must avoid risky experimentation and have no part of frills or fads. The committee advocates no psychological gimmickry nor does it speak for those who see in psychological warfare an independent and somehow magical branch of foreign policy.

It is important to note that this section, nominally a win for George Allen and USIA, who are the consummate “adults in the room”, is aimed squarely at the state department.

Gimmickry, however, is, and always has been, the purview of the CIA. In order for this paragraph to be included, the CIA folks on the committee must have demanded that the condemnation of gimmickry be directed at State.

To really hammer home the point, the CIA and its allies on the committee (e.g., Karl Harr and C.D. Jackson) make perfectly clear that the Committee offers no opinion on “those who see in psychological warfare an independent and somehow magical branch of foreign policy”.

Any government official with half a brain knows that passage is code for the CIA, meaning that the status quo should prevail, which would allow the Agency to continue, and even expand, its covert action programs in this space.

International activities of private persons and organizations

In regard to the activities of private persons travelling abroad, both on their own initiative or on behalf of a private organization, the Committee acknowledges that too much government initiative in this field presents numerous risks. especially since one stated goal was to counter Soviet “front” organizations.

Of course, the CIA itself became a major player in the world of front organizations in the 1960s.

Rather than a wholesale mobilization of private persons and entities, the Committee concludes that “a highly selective approach is necessary.”

This strategy jives with the notion that Jay was selectively recruited for an agent role with the CIA, as opposed to the entire information office being co-opted.

Organization, coordination, and review

The Committee’s report includes, at the end, a series of recommendations. The only area within the scope of this investigation is “the role of the Operations Coordinating Board in psychological and informational matters.”

Allen Dulles was to be retained as Director of Central Intelligence by President Kennedy, so he had a keen interest in the manner in which the OCB operated.

Although Karl Harr, Jay’s cousin and a Dulles acolyte, was set to return to private legal practice, as long as the OCB continued to function in a similar manner as it did under Eisenhower, another vice chairman aligned with the intelligence community could be identified and maneuvered into place.

The Committee report lauds the OCB’s role in coordinating psychological and informational activities, calling its creation “a major step forward”.

At the same time, the Committee recognizes that “the activities of the Board have been the subject of continuing debate.”

Allen Dulles’s fingerprints are all over the following passage:

In the judgment of the Committee it is essential that, whatever changes may be made in national policy machinery, the functions now performed by OCB continue to be provided for.

We believe that the most effective means for insuring the continuation of these functions, particularly those related to psychological and informational matters, is through the continued existence of the OCB.

If the OCB did not exist, it would have to be invented; its creation was the logical outgrowth of the increase in U.S. information activities up to 1953 as well as of the growing importance of public opinion and communications in foreign affairs.

The circular logic of that statement is evident - the function is necessary; if not the OCB effectuating that function, then we would just create another OCB; ergo, we should just continue with the OCB we have in place.

All of that is quite brazen, but it is in the next part that Dulles goes for the kill and, in so doing, commits a fatal error.

Continuing strong Presidential interest in making the OCB effective is the crux of the matter. It is especially important that the President make clear to the individual members of the Board that he expects them to see that matters agreed upon by the Board in the implementation of policy are dealt with effectively in their respective departments and agencies.

In that paragraph, Dulles is attempting to force Kennedy into signing all covert foreign policymaking power over to Dulles.

Read the bold part again. The president is to instruct his department and agency heads, many of whom outrank Dulles (DCI was at the under secretary level), to implement whatever policy the OCB prescribed.

Remember, Dulles controlled the OCB in the late Eisenhower years when he got Karl Harr in as vice chairman, the person who ran the day-to-day functions of the Board.

Karl was leaving, but Dulles clearly believed he could get another Karl in place to run the OCB.

A quick death

I do not know yet whether the incoming Kennedy administration was somehow clued in to Dulles’s mechanism for controlling the OCB (namely, Karl Harr) or if the language about recommendations for the OCB was simply too off-putting.

Perhaps there was some other bias against the OCB. By election day, the Kennedy team was disinclined to continue any initiative propagated by the Eisenhower administration.

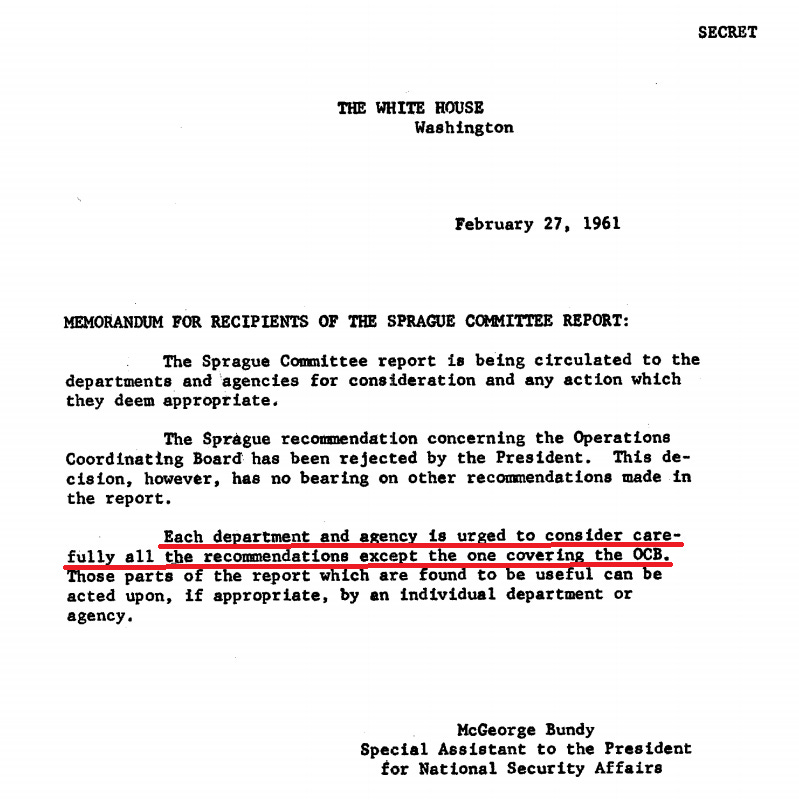

Whatever it was - and I do hope to determine the specifics here - within two months of the report’s publication, McGeorge Bundy, JFK’s National Security Advisory and successor to Gordon Gray, the man who would have chaired the OCB, declared the OCB dead on arrival.

Less than one year, and a failed Bay of Pigs invasion, later, the top three men at the CIA, Dulles included, would be fired.