Fred Dearborn and an Inflection Point in American Covert Operations

White House official's untimely death in 1958 sets off a chain reaction in the National Security Council

If America runs on Dunkin’, then the CIA runs on plausible deniability.

Proving CIA culpability at the level of preponderance of the evidence is extremely difficult. Proving it beyond a reasonable doubt is nearly impossible.

For this reason, researchers focused on the CIA find it instructive to look at fact patterns and make reasonable estimations of probabilities when they reach a fork in the road.

Although not every node in the narrative journey can be proven at either evidentiary level, the broader narrative can, in time, help bring the more uncertain parts of the story into focus.

In this article I will review the facts surrounding the 1958 death of Fred M. Dearborn, who had been a special assistant to President Dwight Eisenhower.

Jay’s cousin Karl Harr was elevated into the role left vacant by Dearborn’s sudden passing.

In a subsequent article, I will build on this material to present an alternative theory of Dearborn’s death and rate this theory’s probability of being true.

Just the facts

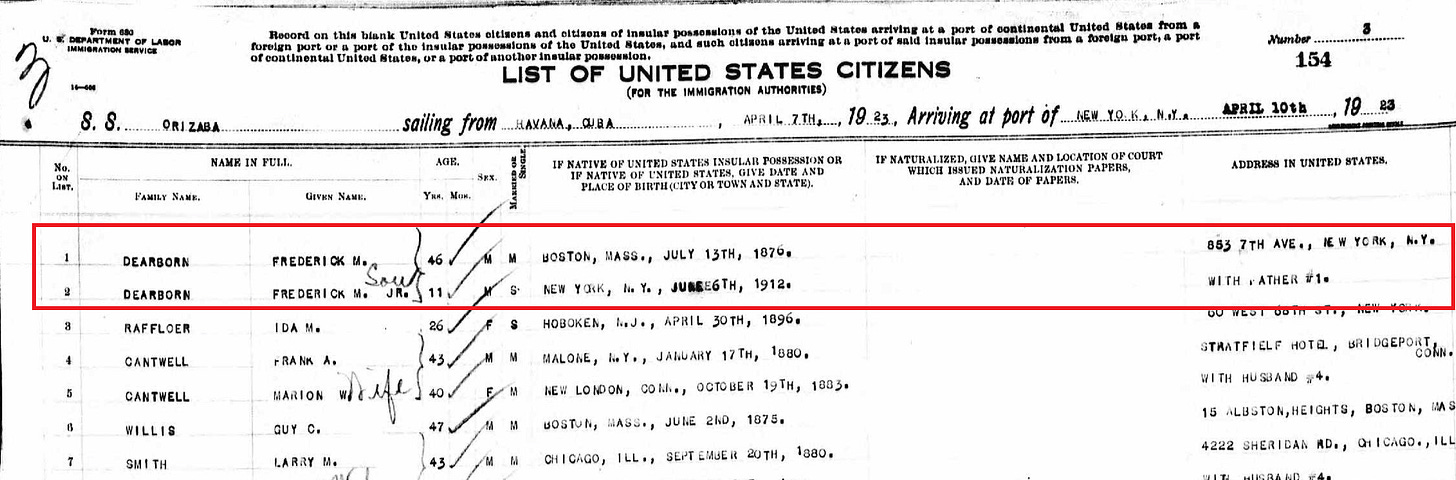

Frederick M. Dearborn Jr. was born on June 6, 1911, or 1912 in New York City. At the time of his death, Dearborn was listed in newspapers as being 45 years old, which suggests he was born in 1912.

However, he appears in the 1911 New York birth registry and many travel records from his childhood and early adult years list him as having been born in 1911, meaning he would have been 46 years old at the time of this death.

Travel records indicate that as a youth, Dearborn travelled to Havana, Cuba with his father, Dr. Frederick Dearborn Sr.

Dearborn’s listed home address on the U.S. Department of Labor form from that trip is 853 Seventh Ave, NY, which is a short walk to Carnegie Hall (located at 881 Seventh Ave).

All of this points to a financially comfortable childhood, a conclusion further supported by the fact that Dearborn attended The Choate School in Wallingford, CT.

Recall that Jay’s neighbor Steven Munger, more than a decade younger than Dearborn, also attended Choate, as did President Kennedy (around six years Dearborn’s junior).

After law school, Dearborn worked as a lawyer in Boston. He served as counsel to Massachusetts governor Christian A. Herter for two years, then followed Herter to Washington when Herter joined John Foster Dulles’s state department.

Beginning in May 1957, Herter was Under Secretary of State and Chairman of the Operations Coordinating Board (OCB), while Dearborn served as Special Assistant to the President for Security Coordination and Vice Chairman of the OCB.

On the morning of February 26, 1958, Dearborn was found dead in “the family home” at 2208 N Street NW, Washington, D.C. of what newspapers termed “natural causes”.

The Boston Globe reported on February 27 that Dearborn’s maid discovered him dead of an apparent heart attack suffered sometime during the overnight hours.

However, the same day the Washington Evening-Star stated that the cause of death was “acute inflammation of the pancreas.”

Dearborn and his wife Pauline had three sons. David (Harvard), Henry and Phillip (North Andover, an elite boarding school) were in Massachusetts at the time of their father’s death.

There is no indication that Pauline was in Washington when her husband died. It is not clear how much time, if any, she spent in Washington.

What is clear, though, is that Fred Dearborn was an outsider in the nation’s capital.

Upon learning of Dearborn’s sudden passing, Eisenhower released a statement saying he was “deeply shocked”. He then ordered that flags on federal buildings be flown at half-staff in Washington, D.C. and Massachusetts.

Dearborn’s funeral was held in South Hamilton, MA. The only federal officials listed as having attended were Christian Herter and Robert Cutler, another Eisenhower security aid and longtime Massachusetts resident.

The other 500 or so funeral attendees appear to have been local to that part of the country.

The situation in Washington

Five weeks after Fred Dearborn’s death, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran an especially astute article concerning the inner workings of the national security state.

Nominally, the topic at hand was government-led propaganda efforts, also known as psychological warfare, but the actual breadth of the article extends much further.

Following another in a string of Soviet propaganda victories, Eisenhower addressed questions about U.S. strategy in this field.

In response to a question about possibly reestablishing the psychological strategy board, which had operated earlier in his presidency, Eisenhower said he didn’t think that was a good idea, adding:

“I do think that we could put possibly an individual probably in one of the departments, possibly in state, where he could have that sole job to do and who would be on the level where he would be cooperating with the Operations Coordinating Board (of the National Security Council) and other places like that all the time. I think maybe we have not exploited the full possibilities of that.”

Eisenhower then noted how much care was given to the establishment of the OCB, and that in the early days C.D. Jackson, a presidential assistant, worked with the Board and directed many of its efforts.

In America, Jackson is considered the original master of psychological warfare. He is also the man who, on behalf of Henry Luce’s intelligence-connected media empire (which included Time and Life magazines), purchased the original Zapruder film the day after President Kennedy was assassinated.

Reached for comment, Jackson told the Post-Dispatch that what is needed is “one experienced man who will carry the torch 24 hours a day to see that all executive departments and agencies understand the foreign policies and do not operate at cross purposes,” adding that it was critical that this person have enough authority to enforce compliance.

C.D. Jackson knew of that which he spoke - he was the first person to serve as a presidential special assistant and vice chairman of the OCB.

In that role, he effectively paired with Under Secretary of State and Chairman of the Operations Coordinating Board Walter Bedell Smith to manage American covert activities. Smith, a military general, had an especially close working relationship with Eisenhower.

Prior to his move to the state department, Smith had been the director of central intelligence. His move is what opened the Agency’s top spot for Allen Dulles.

The Smith-Jackson pairing operated very smoothly, with Jackson managing the Board’s day-to-day work.

It was during this period that the CIA mounted successful coups d'état against Mohammad Mossadegh in Iran and Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala.

Then, things began to slip.

William H. Jackson replaced C.D. Jackson and was not as effective.

Future Vice President Nelson Rockefeller was next in the role, but his pairing with Herbert Hoover Jr. did not work out, as the latter man was reported to have sidelined the OCB in an effort to broaden the state department’s purview.

Next up was Fred Dearborn (emphasis added):

Rockefeller was succeeded by Frederick M. Dearborn Jr., a Boston lawyer, who lacked the qualifications of the two Jacksons. He died in February. Two weeks ago the position was filled by Karl G. Harr, 35 years old, a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University and with the law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell of New York, of which John Foster Dulles and Allen W. Dulles used to be senior members. Since 1954, Harr has held special assistant positions in the state and defense departments. During the war he was an intelligence officer in China and Japan and left the military service as a captain.

(Ed. Note how the article states that Karl was an “intelligence officer in China and Japan” who “left military service as a captain.” It skirts over the branch to which Karl belonged; a minor, but critical omission.)

To place this important paragraph in context, John Foster Dulles was diagnosed with colon cancer in November 1956.

It appears that something about the Herter-Dearborn pairing proved problematic.

Dearborn owed his position and career to Herter, not either Dulles brother.

It is unclear whether Foster Dulles’s cancer was ever in a state of complete remission, but as time passed, it became clear that Herter would replace Dulles once he was too sick to work.

As soon as he ascended to the top spot at State, with his man Dearborn running the day-to-day activities of the OCB, Herter would effectively control the full range of American covert and overt diplomacy.

This was the system implemented by the Dulles brothers. Foster had a direct line to Eisenhower, who would approve the actions they devised.

However, Dearborn died before Foster Dulles, and he was replaced by a worldly, exceedingly well-educated young acolyte of the Dulles brothers, Jay’s cousin Karl Harr.

The delicate dance had begun to shift from a system of State-directed to CIA-proposed covert activities that would enable Allen Dulles to gain 100% of the control that he had previously shared with his brother.

The article continues (emphasis added):

Officials who should know say that Dearborn and Under Secretary of State Christian A. Herter, who succeeded Hoover, cooperated effectively within the limits set by Secretary Dulles. The same is likely to be true with Herter and Harr, although it is difficult to imagine young Harr speaking with the experience and authority of the two Jacksons.

Here, it is important to ask, if Karl could not speak with the experience and authority of the two Jacksons, who benefits?

Whose experience and authority would supersede Karl’s?

The final third of the article details the importance of the Policy Planning Board in any reorganization of the National Security Council’s day-to-day operations.

Robert Cutler, one of the two federal officials to attend Dearborn’s funeral, was Eisenhower’s national security advisor and chairman of the Policy Planning Board.

He was succeeded by Gordon Gray in June 1958. Soon after that, Eisenhower ordered a switch in board responsibilities, pairing Gray with Karl at the OCB. That meant coordination of covert operations would be centralized within The White House.

Thus, the tempered trio from Massachusetts, which at the beginning of 1958 appeared poised to take control of covert operations and subjugate them to the whims of soon-to-be Secretary of State Chris Herter, was fully relieved of this responsibility by mid-1959.

The last man left standing was Allen Dulles, the director of central intelligence.