Around the time that the Sprague Committee’s report was making the rounds in the executive branch of the federal government, Jay and his wife and kids moved into a newly constructed house in a brand-new neighborhood in Bethesda, Maryland.

The house, a four-bedroom, three-bathroom split-level unit at 7208 Blacklock Road offered easy access to River Road, a major thoroughfare that spans from northern Montgomery County down into the District of Columbia, where it merges into Wisconsin Avenue in Tenleytown, NW.

I had long known that one of Jay’s neighbors on Blacklock Rd. was rumored to have been a CIA officer, so I began my due diligence of Jay’s social life there.

The neighbors

Blacklock Rd. is about 250 feet long, with four houses on each side. On one side it dead ends at Selkirk Dr. The other side opens up to St. Bartholomew’s Roman Catholic Church and the accompanying school.

If you walk out the door of the Reid house and look across the street and just a bit to the left on the diagonal, you will see what was in that era the Munger house at 7213 Blacklock Rd.

The Mungers were one of the eight original families on the block. Margery (Midge) Munger was one of Virginia (Ginny) Reid’s closest friends during the nearly three decades that they lived across the street from one another.

Midge’s husband Stephen was nice too, but, like Jay, he wasn’t around as much. I have asked multiple sources about the relationship between the two men. I was told that while they were not exactly friends, Jay and Stephen were always friendly with one another.

By all accounts, Stephen Munger was a good guy, someone who went above and beyond to serve his country. His story is likely very interesting on its own merits, but so much remains clouded in secrecy.

This article leans heavily on the Stephen Munger obituaries published in The Washington Post and the Dallas Morning News following his death in 2004.

One thing that stands out is how much Jay and Stephen had in common.

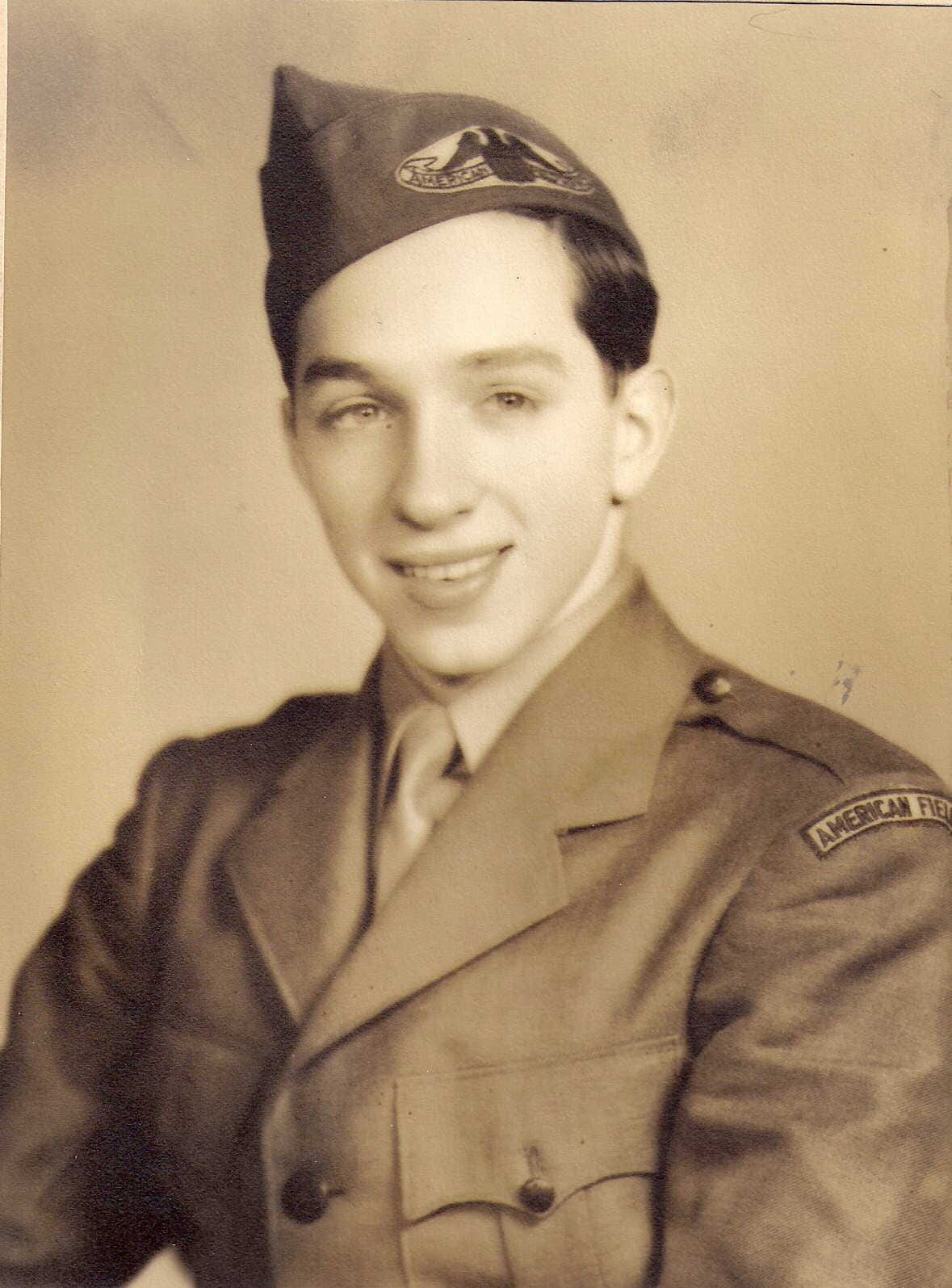

Stephen, who was born in 1925 in California, learned to play polo as a child, and later attended high school at the prestigious Choate Preparatory School in Wallingford, Connecticut. John F. Kennedy, as well as his brother Joe, are among the scores of famous Choate alumni.

A source with knowledge of Stephen’s World War II record told me that, like Jay, poor eyesight, in this case extreme myopia, kept him from serving in the military. However, unlike Jay, Stephen found another way to serve overseas - he joined the American Field Service and drove an ambulance in Italy.

That Stephen would volunteer for such a role, literally picking up the pieces of the war’s human toll, is indicative of the bravery that he would demonstrate throughout his career.

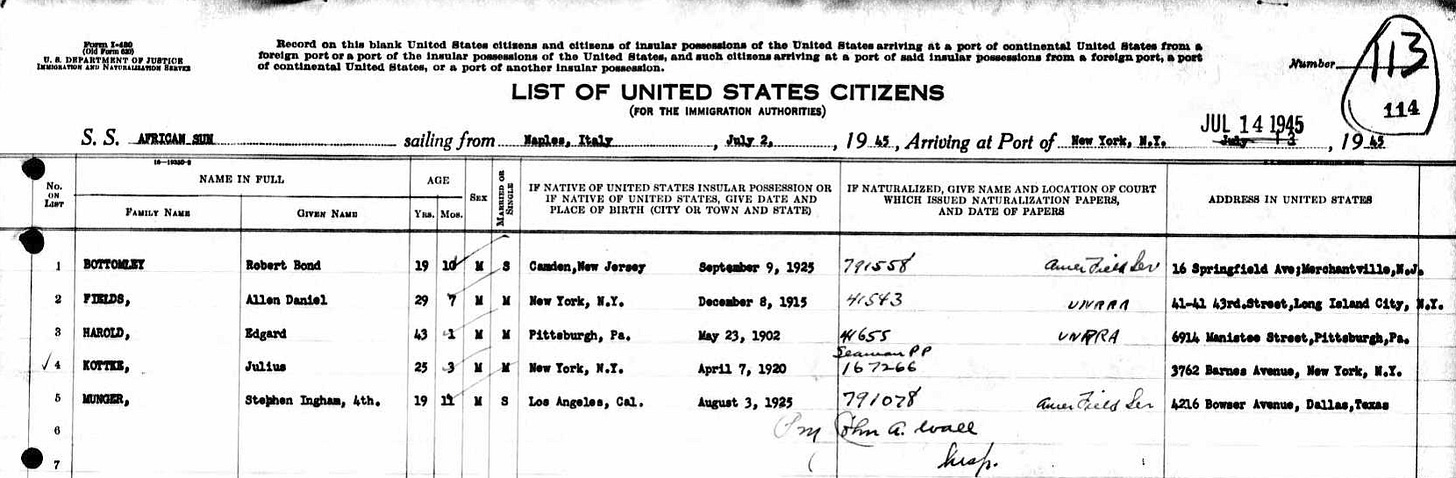

Stephen stayed on in Europe for a few months after the fighting there had ended.

He finally returned stateside in July 1945. His education timeline is a bit unclear, but it looks like he had completed a year of study at Yale before joining the Field Service, then he completed the final three years of his degree after the war.

In 1948, Stephen graduated from Yale, married Midge, and moved to Texas, where his family still lived. The Mungers were one of the more prominent families in Dallas. Munger Avenue, Munger Boulevard and Munger Place, the city's first planned neighborhood, were all named for Stephen’s family.

Again, similar to Jay, Stephen took a job in the newspaper business. His obituaries state that he became a reporter for the Dallas Morning News in 1948. I searched the newspaper’s archives and found one mention of him, but nothing to suggest that he was a reporter in the way that Jay was - writing multiple articles each week.

However, the Dallas Morning News did confirm his employment in its obituary.

After college, he moved to Dallas and joined The News as a book critic and general assignments reporter. He signed up with the CIA two years later.

Given that Stephen was a Yale alum, and Yale has notoriously close ties to the CIA, I do question the timing as to when he formally joined the Agency. I believe it is possible he joined the CIA prior to his stint in journalism, which would have been at the direction of the Agency.

It remains an open question, one unlikely to be answered, but Stephen’s early career path is eerily similar to Jay’s.

CIA service

Stephen’s obituaries list four distinct relationships with the Agency:

Operations officer in Europe - 1950s

Administrative roles at headquarters - 1960s, 1972 to 1985

Operations officer in Vietnam - 1970 to 1972

CIA Contractor - 1985 to the early 1990s

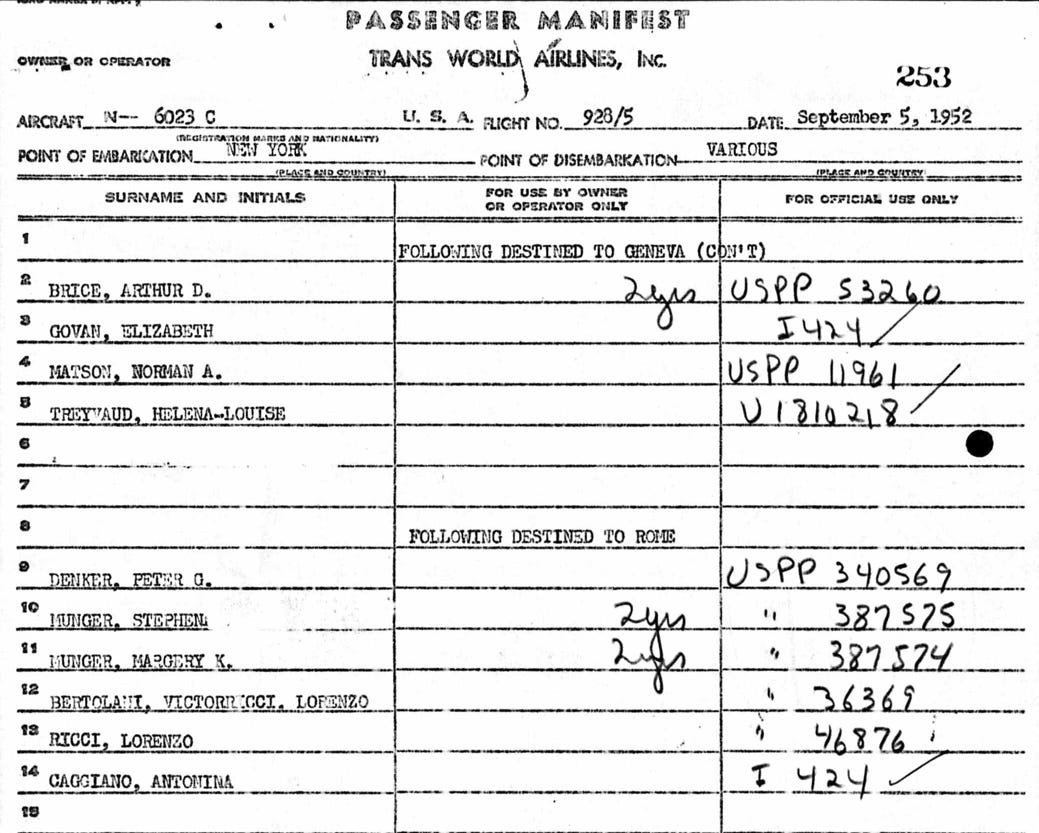

A source with knowledge of Stephen’s time in the CIA told me that he worked in Italy under future Director of Central Intelligence William Colby throughout the 1950s.

Travel documents offer strong supporting evidence, and it makes sense given that he served there during the war and spoke Italian and French.

Like most Agency spouses, Midge Munger almost certainly knew from the beginning that her husband worked for the CIA.

After 30 years as close friends, late in life Virginia Reid did confront Midge Munger about her husband Stephen’s work. My understanding, from those who learned of this conversation after the fact, is that Midge told Ginny she could not talk about it.

Virginia’s suspicions are especially interesting because I believe she is one of only two people in Jay’s private life who may have known about his association with the Agency.

Midge’s refusal to discuss Stephen’s work with the CIA suggests that he was still contracting with the Agency at that time. Virginia died in October 1993. Had she lived just a bit longer, the two women would have been able to have that conversation.

As Stephen’s obituaries state, the couple was finally able to confirm that Stephen had worked for the agency once he fully retired.

The cover question

Stephen told those who asked about his profession that he worked in the “import/export business”. The following anecdote was included in the Dallas Morning News obituary:

[Stephen’s] cousin, Sam Shelburne Jr. of Washington, D.C., said Mr. Munger was not able to admit he was in the CIA until after the operative had retired.

"I once went to visit him in Rome, and he told me he was in the import/export business," the former Dallas resident said with a laugh.

Employing the techniques John Marks details in his late 1970s article “How to Spot a Spook”, I went looking for Stephen’s name in the state department’s foreign registry.

My interest is in Stephen’s CIA stint in Italy, as his Vietnam service is irrelevant to the Jay Reid case. I found his boss, William Colby, listed as a political attaché in 1957, but no mention of Stephen.

The omission of Stephen’s name from the registry list, combined with the explanation that he was employed in the “import/export business”, suggests that he worked under commercial cover.

In 2006, someone filed a FOIA request with the CIA for information on Stephen. The case number was F-2006-00810. I followed up on that request, asking for all documents provided in response. The Agency replied that the requester failed to submit the information necessary to process the request, so no documents were returned.

I sent in the missing information last fall. As expected, it’s been crickets since. That is not a surprise. The agency had not publicly acknowledged that it had employed Stephen, so the FOIA request was doomed to go nowhere.

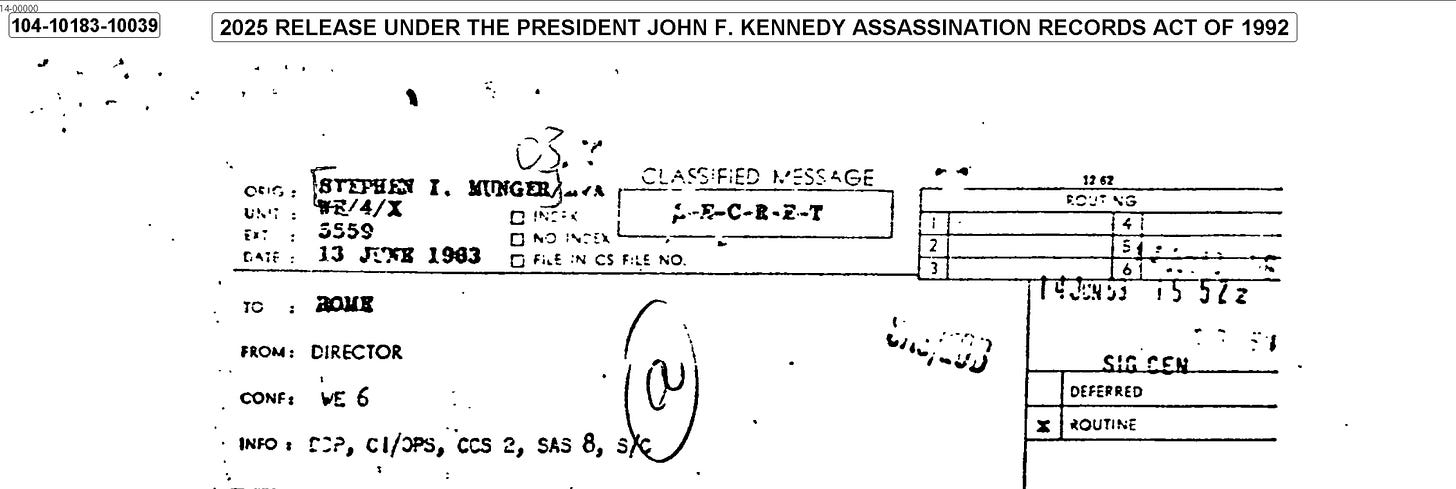

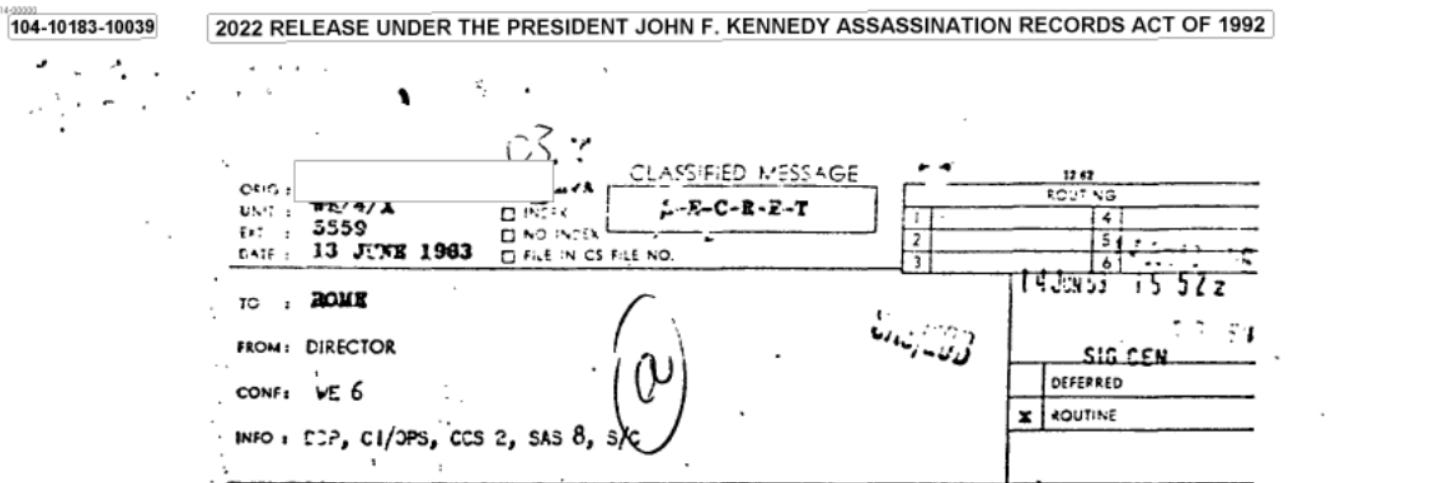

That’s where Donald Trump comes in.

His executive order mandating the release of all remaining documents in the JFK assassination collection caused ripple effects throughout the broader CIA research community. After all, it is through JFK releases over the years that researchers have learned much of what is now known about the CIA during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Most of the redactions that the CIA had insisted on until 2025 were to prevent the release of information pertaining to sources and methods.

Another key concern was the release of heretofore unacknowledged officer names, many of which are found on JFK documents for clerical reasons only.

One such name is Stephen I. Munger. His official confirmation as a CIA officer was among the final redactions removed this spring.

It is important to stress that Stephen’s name on documents in the JFK file does not in any way mean he had anything to do with the assassination. He didn’t.

Rather, it is simply a stroke of luck that he responded to a couple requests for agent traces that came from key offices in the summer and fall of 1963.

Official confirmation of Stephen’s officer status opens up new lines of inquiry, as the Agency can no longer hide behind the dreaded Glomar response of neither confirming nor denying an association with him.

Still, it will be an uphill battle to get any information related to his CIA work in Italy, which, depending on his cover, could be germane to Jay’s case.

The second question - was Stephen working on anything at headquarters related to Jay - should be an easier get, since Stephen’s role was administrative in nature.

Easier is a relative word. The CIA could, and very well may, stonewall my request for another decade or more.

If nothing else, we know that Jay lived across the street from a CIA officer who, as noted in the Dallas Morning News obituary, the Agency recognized as among its finest:

In 1985, he was awarded the Intelligence Commendation Medal for "performance of especially commendable service or for an act or achievement significantly above normal duties which results in an important contribution to the mission of the Agency," according to the CIA.