Fidel Castro and the International Monetary Fund

Two roads diverged at the National Press Club, Fidel took the one less traveled by, and that made all the difference

While the CIA was increasing its espionage and covert operations efforts and the Charms Candy Company was grappling with the impact of political unrest on its sugar-producing partner Arechabala S.A., the Cuban government, led by Fidel Castro as of January 1, 1959, began a tango of sorts with the International Monetary Fund.

Just 10 days after coming to power, Castro appeared on the CBS News program Face the Nation, where he answered questions from a panel of journalists.

In addition to his youthful appearance - Castro was just 32 years old - and the charisma he conveyed in surprisingly fluent English, what immediately stands out in this video is the uncertain nature of his hold on the country.

Within the broader revolutionary movement, there were groups working both with and against Castro’s 26th of July movement, which is important context for his dealings with the IMF.

The Cuban mission

A memorandum from the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs (William Snow) to the Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs (Douglas Dillon), summarized in the Foreign Relations of the United States series, details a February 1959 Cuban economic mission to the United States:

A mission from the National Bank of Cuba is presently in Washington to discuss with the IMF and the U.S. Government the serious threat to the stability of the Cuban peso which results from the fact that following the departure of the Batista administration it was determined that the currency reserve of the country is depleted and $60 million below the legal requirement. The Cuban Government has introduced certain temporary emergency controls on dollar payments and other measures designed to conserve dollar exchange, but considers that assistance from the IMF and from the U.S. is required to restore confidence and to maintain the parity and free convertibility of the peso.

The mission has placed its total need at $100 million. It has requested the maximum standby credit possible from the IMF which is $50 million ($25 million new money, and $25 million renewal) and hopes also to obtain a Treasury stabilization credit. In addition it has indicated its intent to try to borrow from the commercial banks in New York and reschedule short maturities. It is the opinion of the mission that the financial help, if received, will largely serve a psychological purpose and not be drawn upon and that exchange earnings from the current sugar crop will enable the reserves to be replenished.

The renewal included a $12.5 million IMF loan made to Cuba in 1958, when former President Fulgencio Batista was still in power, that was to be repaid in six months.

When the loan came due, the Batista government was in its final stages of complete collapse. Castro inherited responsibility for the repayment.

The mission’s main focus was on securing continued access to international financing and to strengthen the hand of moderates within the Cuban government.

The members of this Cuban mission are well known to various U.S. officials and are regarded as men of integrity and competency, friendly to the U.S. and moderate in their political and economic viewpoints. They are representative of a group of technicians who have been given many posts of responsibility in the new Cuban Government and who are genuinely concerned that anti-American feeling in Cuba might grow. They frankly deplore many of the statements made by certain of the revolutionary leaders and ask for patience and help in order to strengthen the position of the moderates in the present administration.1

Snow recommended that the State Department urge the U.S. Executive Director of the IMF to support the efforts of the Cuban mission.

The talks, however, were not pursued.

Felipe Pazos, president of the National Bank of Cuba, and a member of the Cuban delegation at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, explained how and why the situation changed in a letter to the American Embassy in Havana:

Around the middle of February three officials of Banco Nacional de Cuba visited Washington for several days and held exploratory talks in the International Monetary Fund, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and various Departments and Agencies of the United States Government. The visit took place at the initiative of Banco Nacional de Cuba with the knowledge of the Cuban Government and had as its purpose to explore the possibilities of obtaining financial assistance to restore and strengthen confidence in the Cuban peso, which had been undermined by the severe depletion of our international reserves [which] occurred during the Batista régime. The financial support sought was mainly in the form of currency stabilization agreements with the International Monetary Fund and the United States Treasury Department.

Our officials found in Washington a most warm and sympathetic reception, and returned to Cuba deeply impressed with the sincere spirit of understanding and cooperation they found in every quarter. But the talks were not pursued for two reasons: first, because the lack of confidence in the currency which was the concern which prompted our request did not increase, but rather subsided, [sic] And second, because at the time of our talks in Washington, we were not prepared to commit ourselves to the specific economic and financial policies and measures required by the International Monetary Fund, to whose action the United States Treasury Department had tied its own assistance.2

In short, Cuba did not pursue the economic assistance discussed in Washington D.C. a couple months earlier because the strings that would have come attached to any agreement were considered too stringent.

Even though it was not entirely clear at the time that Castro would soon lead Cuba into the communist orbit, in retrospect, the members of the Cuban mission do appear naive in their aspirations to secure financing from New York City banks.

Pazos, in his letter to the embassy, goes on to explain that the situation has changed - unemployment was rising and the Cuban economy was slowing down.

He writes that with Castro set to visit Washington later that month, should the economic assistance talks resume, they would no longer be centered on restoring confidence around the Cuban peso, but rather spending on infrastructure and other projects that could help stimulate the Cuban economy.

Nine days later, Castro arrived in Washington and proceeded to charm many in America’s capital city.

Fidel Castro in Washington D.C.

One of Castro’s events took place at the National Press Club. An April 17th dispatch from The Guardian newspaper in the United Kingdom provides useful context on the new leader’s meeting with the American press:

Castro has come to the United States primarily to address the American Society of Newspaper Editors tomorrow afternoon. Even this invitation has provoked a measure of controversy. The State Department - which was overwhelmed by surprise when Castro swept Batista into oblivion - at first murmured sad doubts about the wisdom and propriety of inviting Castro at this time. This official timidity led some nervous editors to complain to their society. Its president, Mr. George W. Healey later announced with some pride that the State Department fully agreed that the invitation was justified. This pride seemed utterly misguided and misplaced to more valiant editors. They sternly told Mr. Healey that it will be a woeful day for freedom if the society must seek the State Department’s advice and approval before it issues an invitation to a foreign statesman.3

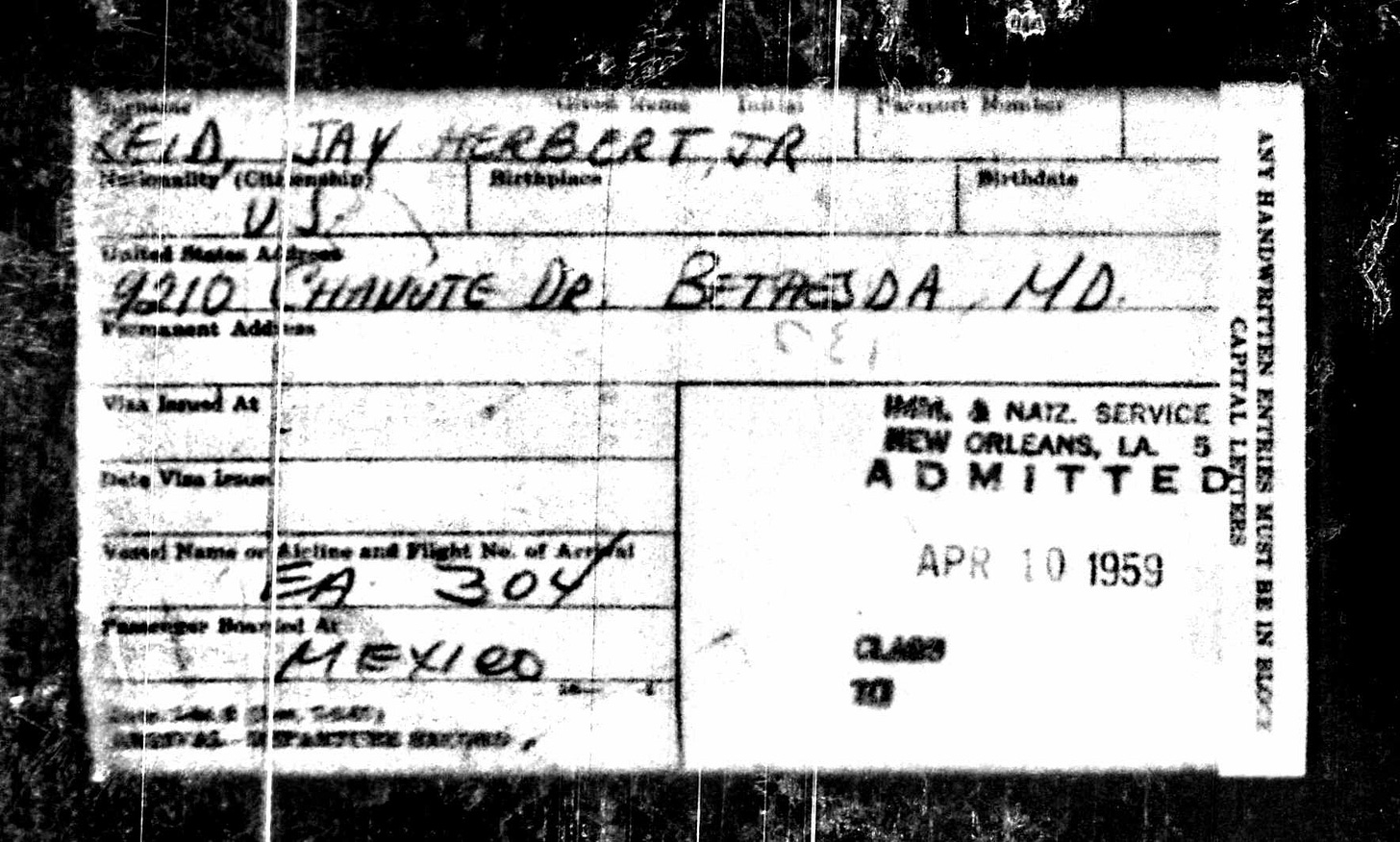

Jay had returned on April 10 from an extended trip in Mexico, which hosted the UN Economical and Social Council meetings. He passed through customs and passport control in New Orleans, presumably on his way home to Bethesda, Maryland.

Given that Jay was a member of the National Press Club, and the IMF was in active talks with the Cuban government, it is likely that Jay attended Castro’s speech. However, at this time, I have not located documentary evidence that would confirm his attendance.

The video segment above, from Castro’s National Press Club speech, ends with Castro making an important statement. In response to media speculation that he came to America hat in hand, Castro says that his trip to Washington was born of friendship. While he would like to secure financing to help stabilize his country’s economy, he is not a man whose ideas can be bought.

In the span of 60 seconds, Castro had every American in attendance rolling on the floor in laughter, only to be firmly cleansed of any thoughts they may have entertained that Castro would answer to anyone in the United States.

Reverberations

Later in the trip, Castro appeared on NBC’s Meet the Press and proclaimed that he was not a communist, that indeed he supported democracy in its purist form, “humanism” as he called it.

One month later, the Cuban government forced through an agrarian reform bill that called for the expropriation of foreign owned farms and sugar plantations.

Before the end of the year, Eisenhower would order to the CIA to develop an operation to remove Castro from power.

Needless to say, no economic assistance package ever came into being.

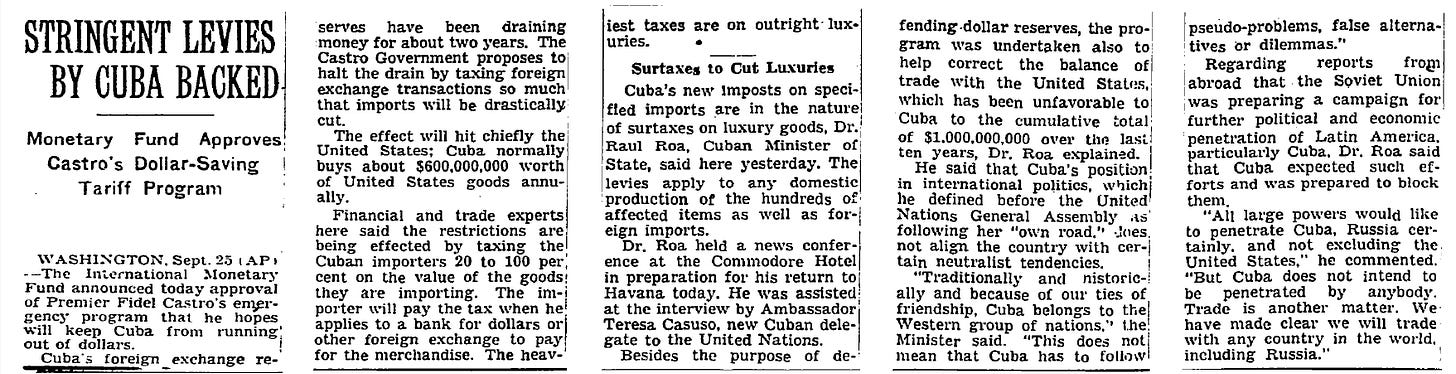

The IMF did cooperate with Castro on a separate economic initiative - a tariff levied on currency exchange, which was an attempt to conserve U.S. dollars - in the fall of 1959.

As for the 1958 IMF loan, the Cuban government repeatedly delayed making payments.

When the balance due was still outstanding in 1963 (with interest charges piling up), the IMF’s rules required its managing director to take action that would prohibit further use of the Fund’s resources. That process dragged on for several months, until Cuba renounced its membership in 1964. Nonetheless, over the next five years, the Castro government gradually repaid the full amount due, including all interest charges.4

Decades later, Castro told Citigroup executive Bill Rhodes that he regretted the decision to leave the IMF.

Rhodes recounted that Castro told him Cuba should have stayed a member not only of the IMF, but also the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. "And he said that was a poor decision, because they're institutions that could have helped Cuba, you know, in our economic problems."

…Long-time Cuba followers may be even more startled by Castro's other admission: that he felt it was a mistake to put Ernesto "Che" Guevara in charge of the Cuban central bank [Che succeeded Felipe Pazos].

"He said, 'Why I ever did that, I don't know, because obviously Che Guevara knew nothing about finance and banking,' but he said, 'I put him in there because I guess I trusted him. But it was a mistake.'"5

Any notes concerning internal IMF deliberations on the Cuba question are likely housed in the IMF Archives in Washington, D.C. I hope to unearth them the next time I am in town.

“Memorandum From the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs (Snow) to the Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs (Dillon,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960, Cuba, Volume VI. February 20, 1959.

“Memorandum From the President of the Cuban National Bank (Pazos) to the Embassy in Cuba,” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960, Cuba, Volume VI. April 7, 1959.

Freedman, Max. Fidel Castro Visits Washington, The Guardian. April 17, 1959.

“Will Cuba Rejoin the IMF?” World Economic Forum, January 9, 2015. Accessed November 26, 2024.

Caruso-Cabrera, Michelle. “Startling Admissions: Fidel Castro Shared Financial Regrets in the 1980s,” NBC News. April 15, 2015. Accessed November 26, 2024.