Original Sins

Hidden and not-so-hidden hands shape the International Monetary Fund in its early days

Like most organizations, what the International Monetary Fund would do in practice depended on two key factors:

Where it would be located

Who would lead it

As the war approached its end, the time came to turn drafts for the IMF and its proposed sister organization, the World Bank, into actual institutions.

This process would collide with the political undercurrents of what would soon become the Cold War, as countries, national agencies, and individuals all jockeyed for power.

The foremost expert on how this all came together to form the IMF is James Boughton, historian emeritus at the Fund and author of numerous works.

Boughton’s book Harry White and the American Creed: How a federal bureaucrat created the modern global economy (and failed to get the credit), along with David Talbot’s The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government (which cites Boughton’s earlier works) provide useful context about the levers of power being pulled behind the scenes, and the ultimate goals of those involved.

Location, location, location

The two major architects of the IMF are both known by their full names - Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes - but their relationship is as misunderstood as Harry’s name.

White technically did not have a middle name. He merely adopted “Dexter”.

Likewise, Keynes, though an outspoken eugenicist, is fondly remembered as a titan of the economics field, while White, to the extent that non-economists remember him at all, is still connected to a series of accusations of communist subversion.

However, during the war, White was the senior partner, owing to the comparative power disparity between hanging-on-for-dear-life Great Britain and the United States, an emerging superpower.

Keynes first pushed for the IMF’s headquarters to be in London, but when that idea did not gain any traction, he tried to negotiate for New York. Keynes was “adamantly opposed” to locating the Fund and the Bank in Washington, D.C., where the U.S. government could easily interfere with both organizations’ work.

As Boughton writes, Keynes believed that:

Political influence would be harder to sustain [in New York]. He carried that fight all the way up to the individual governors’ meeting, which took place in Savannah, Georgia in March 1946…Harry was also aware that the U.S. banking lobby was adamant that the headquarters should be in New York.1

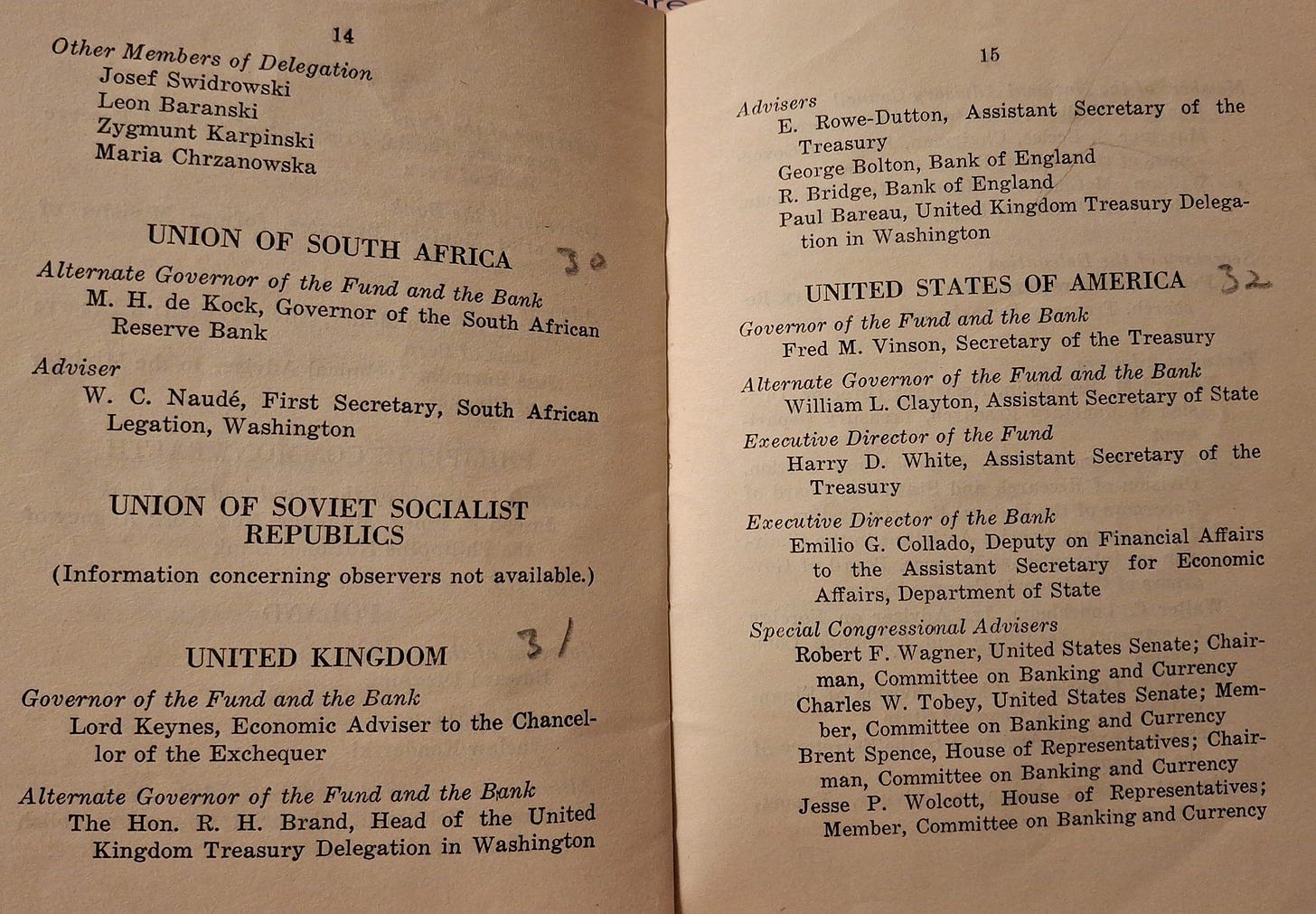

The clinching factor was the death of Franklin Roosevelt in the spring of 1945. FDR’s longtime Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, was pushed out a few months later. He was succeeded by Fred Vinson.

Although Vinson named White the first U.S. Executive Director, that was actually a demotion, which meant White would not be dealing on Keynes’s level in Savannah. That would be left to Vinson.

White and Vinson did not share the kind of close working relationship that White had with Morgenthau. As a result, White’s influence on Fund-related decisions declined.

Vinson was free to choose the headquarters location for both institutions, and he chose Washington, D.C.

The decision was presented to Keynes as a fait accompli.

In one of the great rhetorical flourishes for which he was justly famous, Keynes used his governor’s speech in Savannah to warn of the consequences. In time, he warned, Carabosse - the wicked fairy Godmother in Sleeping Beauty - could slip in and pronounce a curse on the IMF and the World Bank: “You two brats shall grow up politicians; your every thought and act shall have an arrière-pensée; everything you determine shall not be for its own sake or on its own merits but because of something else.”2

Dirty Tricks

It was kill or be killed in the pivotal summer of 1948.

The House Un-American Activities Committee’s pursuit of former State Department official, and accused Soviet spy, Alger Hiss was a major story nationwide.

Privately, Richard Nixon, then a young congressman and HUAC member, harbored doubts about the case against Hiss.

On the morning of August 11, Nixon called John Foster Dulles in his office at the law firm Sullivan & Cromwell (the same firm where Karl Harr would work beginning in 1950, when he completed his Ph.D. as a Rhodes Scholar).

It was a presidential election year, and New York Governor Tom Dewey appeared to have the upper hand in his matchup with the incumbent, Harry Truman. It was well known in political circles that Foster Dulles would be Dewey’s pick for Secretary of State, in the event that he should win on election day.

Nixon and Foster had a history. As a law student, Nixon had pursued a career at Sullivan & Cromwell, but had been turned down by the same man he now hoped would help bail him out of the political mess that was the Hiss case.

This time, as Nixon knew, Foster had reason to play ball. In his testimony, Hiss reminded the Committee that it was Foster, as chairman of the board, who had offered Hiss the role of president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a title Hiss still held during the hearings.

By name dropping Foster, Hiss became a threat to Foster’s political future.

Foster agreed to meet Nixon that evening.3

When Nixon walked into Suite 1527 at the Roosevelt Hotel that summer night in 1948, he faced a formidable array of power. With Foster were his brother Allen, Christian Herter [who would succeed Foster as Secretary of State in 1959], and Wall Street banker C. Douglas Dillon, who would later serve President Eisenhower in the State Department and presidents Kennedy and Johnson as Treasury secretary. These men made up a significant section of the Republican Party’s ruling clique. If Nixon failed to convince them that he had a solid case against Hiss, HUAC would have to close its noisy show, and his political career would be wrecked just as it was gaining traction.4

Nixon hated Hiss, who at one point, in reply to Nixon’s relentless questioning, had said, “I am a graduate of Hard Law School. And I believe yours [Nixon’s] is Whittier?”5

Once they read the transcripts of Committee testimony, the four Republican luminaries knew they had a major problem on their hands. They decided to circle the wagons.

Nixon continued his tough questioning in Committee hearings, Foster Dulles convinced Hiss to resign his position at the Carnegie Endowment, and Allen Dulles began feeding Nixon incriminating intelligence in an effort to strengthen the congressman’s case.

Some of this confidential information about Hiss likely came from the Venona project, the Army intelligence program that had been set up in 1943 to decrypt messages sent by Soviet spy agencies. The Venona project was so top secret that it was kept hidden from President Truman, but the deeply wired Dulles might have enjoyed access to it.6

On August 13, two days after the meeting between Nixon and the Republican luminaries, the Committee’s top target - Harry Dexter White - was scheduled to testify.

There is little doubt that Harry Dexter White was one of the main topics for discussion, along with Alger Hiss, at the Roosevelt Hotel that night in August 1948. In fact, the Dulles group saw White as a bigger threat to their postwar plans than Hiss. The formidable White was intent on building a new financial order that would be a “New Deal for a new world,” with the new global institutions channeling investment to needy countries in ways that produced the broadest public good rather than the greatest private gain. When the Roosevelt administration unveiled its plans for the World Bank and IMF, Secretary Morgenthau declared that the goal was “to drive…the usurious money lenders from the temple of international finance.” Not surprisingly, Wall Street banks saw the new institutions, which were to be “instrumentalities of sovereign governments and not of private financial interests,” as dangerous new competitors in the global capital markets.7

The problem with White was two-fold.

First, at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, White and Morgenthau tried to position the nascent IMF and World Bank as replacements for the Bureau of International Settlements (the BIS, known as the central bank of central banks), which they saw as too beholden to banking interests in New York, London, and Nazi Germany.

Although the threatened interests were able to rally and successfully defend the BIS, White had showed his hand. And concerns in these quarters only increased when White pushed to admit the Soviet Union into the IMF and World Bank.

Second, White had dirt on Allen Dulles. As Morgenthau’s right-hand man at Treasury, he had seen the receipts outlining the Dulles group’s financial collaboration with Nazi Germany.8

White defended himself vigorously before the Committee, but his health was already failing, and the additional HUAC-induced stress no doubt contributed to the fatal heart attack he suffered days after testifying.

Although by 1948 White’s health issues and the communist whisper campaign had conspired to successfully remove him from his perch at the IMF, White was still an advisor to the organization he created, and as such he held outsized influence.

His passing sealed the Fund’s fate.

It was now under the control of politicians and banking interests.

Boughton, James M. Harry White and the American Creed: How a federal bureaucrat created the modern global economy (and failed to get the credit). New Haven: Yale University Press. 2021. Pg. 210.

Ibid. Pg. 211-212.

Talbot, David. The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government. HarperCollins: New York, 2015.

Ibid. Pg. 170.

Ibid. Pg. 168.

Ibid. Pg. 171.

Ibid. Pg. 177-178.

Ibid. Pg. 178-179