In 1923, roughly three years after signing a partnership deal to sell sugar to the Charms Company of Bloomfield, NJ, which was started by Jay’s uncle, Walter W. Reid Jr., Spanish tycoon Jose Arechabala died. He was 75 years old.'

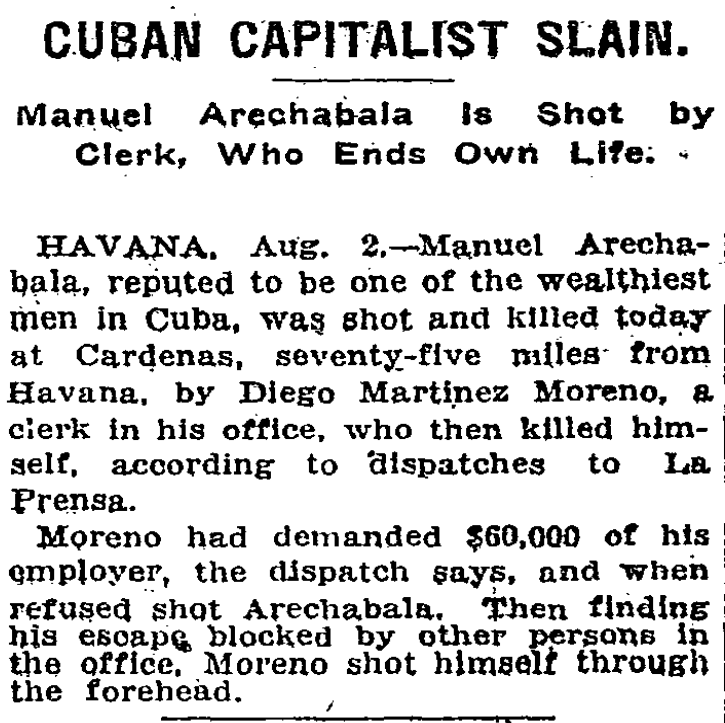

Control of Jose’s business conglomerate, Arechabala S.A. passed to Manuel Arechabala, whose relation to the founder is still unclear.

On August 2, 1924, Manuel, then one of Cuba’s richest men, was reportedly shot and killed by an Arechabala S.A. clerk, who had demanded $60,000. The clerk, lacking a means of escape after shooting Manuel, then turned the gun on himself.

In 1926, Manuel’s successor, Gabriel Malet y Rodriguez, died while still a young man, leaving the company at a crossroad.

Inter-war expansion leads to post-WWII peak

This leadership turmoil ultimately proved just a bump in the road, although it did lead many heirs to the Arechabala fortune to flee for Spain.

José Fermín Iturrioz y Llaguno, known as "Josechu", who was the son of one of the founder’s nieces, took the reins of the company in 1926.

At the time, Cárdenas was still in the midst of an economic decline that had commenced before the turn of the century. The New York stock market crash was only 3 years away and the United States was in the middle of Prohibition, which would last from 1919 until 1933. Cárdenas had lost much of its industrial base, with its railroad company being moved to Havana, while suffering the corresponding loss of population and wealth, which also moved to the capital…

The decades-old decline of the Cárdenas economy was due in large part to the shallowness of the city's harbor. As sea vessels had continued to grow in size and draught, the harbor had become more and more obsolete, causing international shipping companies to forego Cárdenas as a Cuban trade port, in favor of Havana and Matanzas. An expensive system involving the use of lighters for loading and off-loading the larger trade vessels had become necessary at the port, adding tremendously to the cost of water transportation through Cárdenas.

As far back as colonial times there had been plans drawn and efforts made to deepen the port, but the job had never been done. This noble quest had even spawned a major scandal in late 1924, when a group of wealthy political insiders had ramrodded a law through the Cuban legislature under which they were to obtain $700,000.00 from the government to deepen the harbor, build a breakwater port (jetty), and be granted a 50-year monopoly over all shipping through the port of Cárdenas. The project was later stopped by the new revolutionary government of Gerardo Machado, but the money disappeared and the job was left undone…

In 1931, the company opened one of the world’s first sustainable fuel plants, which produced a form of ethanol. During World War II, Arechabala ethanol comprised nearly half of Cuba’s total fuel consumption.1

Following a 1933 hurricane that brought mass destruction and had serious negative financial consequences for Arechabala S.A”

Iturrioz and [his lead engineer] set out to finally remedy the problem that was as old as Cárdenas itself. José Arechabala, S.A., having proven itself a dependable and capable enterprise, would take on the job of deepening the harbor and constructing a modern and permanent port facility. Arechabala marshalled engineering talent, equipment, and the manpower necessary for this immense job and began dredging the harbor and constructing the "Espigon" (jetty) in 1939. For four years, countless Cardeneses were employed in this monumental task. By 1944 the job had not only been completed, but Cárdenas had also received a new shoreline with a seaside drive, a seaside walk, new green spaces, a marina, and a monument commemorating the first raising of the Cuban Flag on Cuban soil.2

In 1934, Arechabala S.A. launched Havana Club Rum, which would later become its signature product. It also marketed numerous other rums and liquors.

In 1936, possibly in connection with the Charms Company partnership, Arechabala S.A. opened its own candy factory in Cardenas, where it had 148 acres of land along the coast.

Business boomed for Arechabala S.A. throughout the 1950s. During this time, the company’s holdings included:

Sugar warehousing capacity of 2 million 325 lb. sacks

One of the oldest and most productive sugar refineries in Cuba with fully modernized equipment

A very high quality-controlled candy manufacturing plant

Syrup plant

Molasses plant with capacity for 5 million gallons

Cuba's oldest and largest distillery of alcohol, spirits and rums

Aging cellars for millions of liters of rum

Liquor manufacturing plant

Barrel manufacturing plant

Petroleum plant

Hydrocarbons plant - pioneering the use of alcohol as a motor fuel

A coastal trading ship line

A maritime terminus

Shipyard (initiated during WWII when ships for trade with the U.S. were scarce).3

Then, it all came crashing down.

The Revolution

Fidel Castro took power on January 1, 1959. By the summer, he was taking steps toward converting the economy to communism.

Meanwhile in Cardenas, Calixto Lopez, the town messenger boy, seizes Arechabala Industries and Havana Club for the Revolution. He points a machine gun at [recently married] Ramón [Arechabala] and exclaims, “I am Pepe!” – referring to Ramón’s uncle, the then-president of José Arechabala S.A.

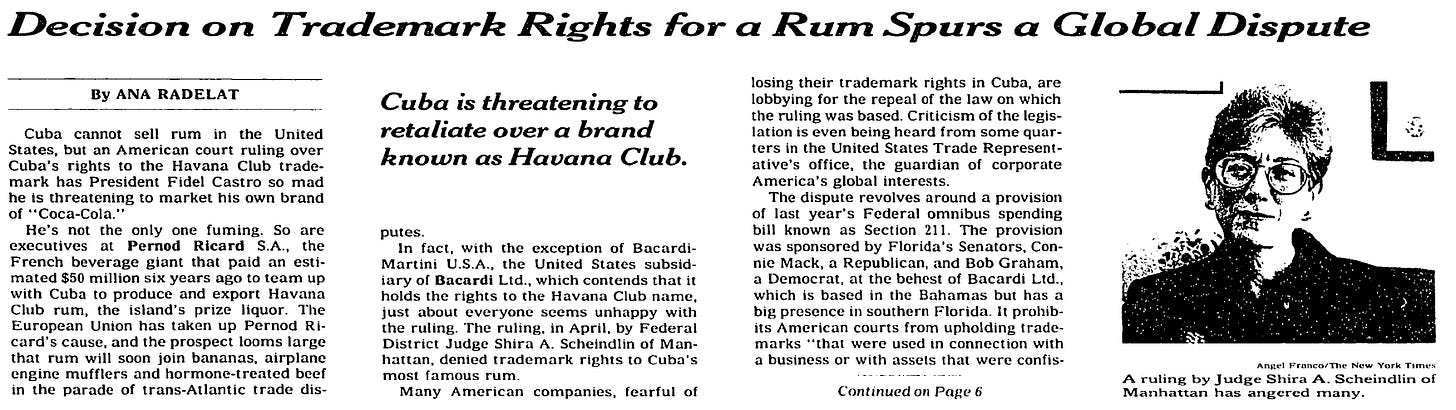

Following the expropriation of the Arechabala business empire, the now government-run enterprise sold its own version of Havana Club Rum, using a different recipe and omitting any mention of the Arechabala family.

Ramon Arechabala stayed and oversaw the distillery’s operations until 1963. More than 50 years later, his wife, Amparo, described the circumstances that finally forced them to leave.

“We didn’t decide to leave Cuba. It was decided for us by the Castro regime…They took Ramon and threw him in jail. They then gave him three choices. One, you can stay and work in the fields; two, we will release you from jail, but we’ll find another reason to arrest you; or three, leave Cuba.”

As their plane departed Cuba, bound for Spain, Amparo said, “I told Ramon to look outside the airplane window because we are never going to see this country again. That was my last recollection of my beloved country,”

Behind the Label

Ramon became the keeper of the flame, so to speak. He never stopped fighting to regain control of the company, and the valuable Havana Club Rum trademark, that Castro and the Cuban government had confiscated.

For a behind the scenes look at the battle to recover Arechabala S.A., which has descended into what the media has termed the rum war, I highly recommend watching the first four parts of a brief documentary called Behind the Label. Each part requires attestation that the viewer is at least 18-years old because the topic is rum, so I could not embed the videos, but these links will take you to the videos on YouTube:

U.S. Government focus

Considering how large the Arechabala S.A. organization was at its peak in the 1950s, how much money and power the family had, and what it stood to lose when Castro took the country down the communism road, I hypothesized that someone within the family, or otherwise high up in the organization, would have been in touch with the CIA.

To date, I have not found any declassified Agency documents to that affect. At a time when the CIA was coordinating counter-revolutionary activities among the major sugar companies, Arechabala S.A. appears conspicuously absent.

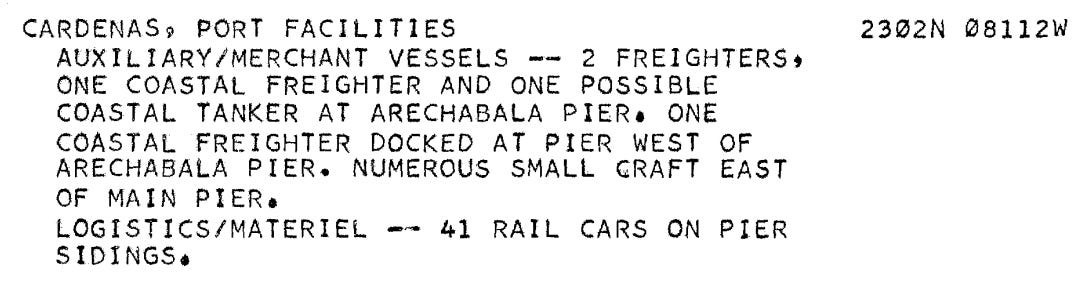

The only mention of the company that I have seen in declassified CIA documents relates to a series of port activity reports in the spring of 1962.4

In contrast, the plight of the Arechabala family has been in the congressional spotlight for decades.

On July 13, 2004, Ramon Arechabala testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee. His testimony on record includes this suggestive passage (emphasis added):

My family never gave up hope of getting our rum business back. The rule of law, we felt sure, would be restored to Cuba and with it, our stolen property. In the meantime, I worked at odd jobs in Cuba. But every time my business showed signs of getting off the ground, the government closed me down. My background made me unreliable, particularly after the Bay of Pigs. Eventually, I was thrown in jail by the Castro government after I organized a party for foreign embassy employees. My jailer then gave me a choice, leave Cuba or face the prospect of staying in jail indefinitely on some phony charge.

I read that as Castro’s government suspecting Ramon of having ties to foreign intelligence. If I were in the government’s position, that would be my suspicion too. Why else would Ramon stay and “work for free” after the expropriation of his family’s business, as he stated in his testimony?

Ramon and Amparo Arechabala are now both deceased, but the government continues to cite their case in ongoing legislative debates.

California Congressman Darrell Issa entered this passage into the Congressional Record on November 13, 2023.

Although still unconfirmed, my suspicions about possible Arechabala family connections to the CIA, especially on the part of Ramon, remain.

FOIA will render the ultimate verdict.

Havana Club, Our Story. Accessed 11/19/2024.

Arechabala Industries, family history. Accessed 11/19/2024.

Ibid.

Central Intelligence Agency: May 2, 1962; May 22, 1962; May 29, 1962 copy of the original May 22, 1962 report (with added notations); NPIC Copy of the May 22, 1962 report