Some of the most sensitive discussions regarding covert operations took place during the last two years of Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency.

In recent weeks, I have shown a spotlight on the Reid family’s links to Fidel Castro’s revolution in Cuba, as well as the American response:

Jay Reid’s cousin, Karl Harr, served as a Special Assistant to the President and was Vice Chairman of the Operations Coordinating Board from 1958-1961.

Jay’s father was a co-founder of the Charms Candy Company, and his cousin, Walter Reid III, led the organization during this time.

The CIA, as part of its HTLINGUAL operation in the mid-1960s, was reading the mail of Melvin J. Gordon, leader of the Tootsie Roll Company, which would acquire Charms in 1988.

The CIA stepped up its activity in Cuba in 1959 as Castro implemented an agrarian reform program that threatened the island’s sugar companies, one of which, Arechabala S.A., had an ongoing partnership with Charms.

Late in 1959, the communist government expropriated Arechabala S.A., later jailing its lawyer and sending other Arechabala family members into exile.

In 1959, Castro was in talks with the International Monetary Fund about the repayment terms for a loan taken the prior year by the Batista government. Castro also sought economic aid from the U.S. government, U.S. banks, and the IMF.

The final piece of this particular puzzle, just one of many involving Jay and the CIA, is a detailed examination of the decisions taken by the Operations Coordinating Board as well as the broader National Security Council, where Karl Harr played critical roles.

In order to fully grasp Karl’s positioning and allegiances within these government bodies, it is important to understand his background.

Karl Gottlieb Harr, Jr. was born in South Orange, New Jersey in 1922. Just as in Jay’s family, Karl was given his father’s name while his sister, Mildred, took his mother’s name.

Mother Mildred was a sister to Jay Reid Sr. and Walter Reid Jr., making her Jay Jr.’s aunt.

Karl Sr. worked for Charms, the Reid family candy company, for 35 years.1 Although he died before the Cuban Revolution, his extended employment opens up the possibility that the Harr family held Charms stock.

Charms remained a privately held company until it was sold to Tootsie Roll, so the limited stock shares would in time prove very valuable.

A product of Columbia High School in neighboring Maplewood, NJ - which at the time was considered one of the best public schools in the country - Karl graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Princeton University in 1943.2

At Princeton, Karl played varsity football, was vice president of the Cottage Club, and chaired the undergraduate committee.

Other Cottage Club alumni include:

Secretary of State John Foster Dulles (1914)

Author F. Scott Fitzgerald (1917)

Academy Award Winning Actor Jose Ferrer (1933)

Heisman Trophy Winner Dick Kazmaier (1952)

On a campus of high achievers, Karl stood out as an elite academic talent.

Princeton’s long, dark history with the CIA

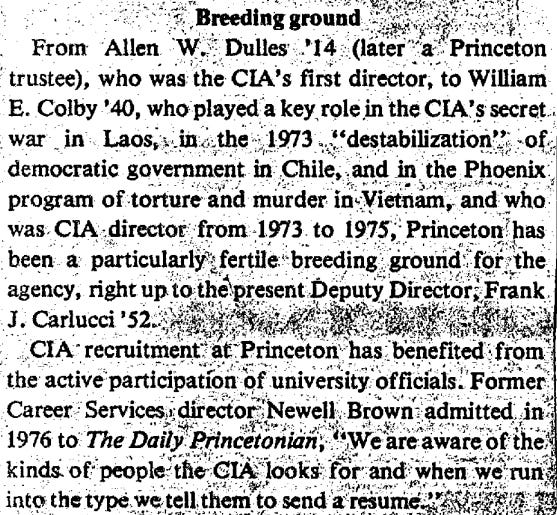

Dating back to the Office of Strategic Services (or OSS, the wartime spy organization that preceded the CIA), Princeton University has been a breeding ground for covert operators.

An article published in The Daily Princetonian on November 12, 1979, and released via FOIA by the Agency in 2005, details the sordid intermingling of the spy service and the Ivy League institution.

The student-authors did not pull any punches in their lengthy expose. I highly recommend reading the entire article, which can be found in PDF form below.

From illegal domestic spying to the MK-ULTRA mind experiment program, Princeton has been along for the ride from the very beginning.

As it happened, the OSS was in many ways a Princeton operation. In World War II, the bureau chiefs in New York, Berlin, and London were Princetonians, as were its general secretary and its chief cryptologist.3

In the 1940s and 50s, the clandestine service’s rationale for recruiting at Princeton was two-fold:

First, the humanities and social sciences programs produced graduates with elite analytical skills.

History professor Joseph Strayer was a charter member of a key advisory group known as the Princeton Consultants. As CIA Director Allen Dulles 1914 once noted, the real value of Strayer’s prominence as a medievalist was — just like the intelligence process — the ability to base reliable conclusions on very few facts. In a declassified article in the CIA’s internal journal, Strayer advised peer academics to insist on standards of precision and almost a scorching objectivity, urging fellow professors to challenge hidebound assumptions (a characteristic rarity within the CIA) and simply tell the truth.

Second, personality traits found in ideal recruits matched closely with the university’s clubs (emphasis added).

The "playing fields" of Ivy League schools [were] elitist training grounds for future recruits. At Princeton, it has long been known that Deans Lippincott and Brown culled through student records for candidates. The roster of Princeton alumni CIA case officers…suggests a preference for members of the more selective eating clubs — Ivy and Cottage, followed by Cap and Gown. At least back in the day, Princeton’s Bicker process allocated eating billets according to a hierarchy that F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 might have summarized best for recruiters — e.g. depicting Cottage as “an impressive mélange of brilliant adventurers...”4

Ivy League professors played an outsized role in guiding the brightest students toward employment opportunities in the intelligence world.

Among intelligence agencies like the CIA, the phrase “the P source” — short for professor source — used to be code for the professors and university administrators who recruited on their behalf. For a time, Ivy League schools like Princeton supplied “a disproportionate amount” of the new employees to the CIA and predecessors like the Office of Strategic Services, the OSS, according to the CIA’s in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence. These pipelines informed the culture and reputation of intelligence agencies: FBI agents called OSS analysts “Oh, So Socials,” a crack about their genteel grooming in eating clubs and secret societies. (In turn, OSS analysts called their flatfoot FBI colleagues “Fordham Bronx Irish.”)

Allen Dulles, who appears to have played a profound, if hidden, role in Karl’s career trajectory, evangelized on the skills he considered essential for intelligence work (emphasis added):

Reading as a historian entails learning how to look for information about how people put together the information you’re looking at. Allen Dulles 1914, the first civilian director of the CIA, was a history major at Princeton. In 1941, he started working for the OSS in Switzerland, sending covert reports to his classmate, John C. Hughes 1914, the head of the Service’s New York bureau. (His brother, John Foster Dulles 1908, majored in philosophy before making his way, too, to the OSS and eventually becoming secretary of state under President Dwight Eisenhower.) Allen Dulles rose through the CIA’s ranks in the 1950s; throughout his career in the Agency, he sought insights from humanities scholarship. During the 1960s, he met several times a year on Princeton’s campus with a group of humanities professors, whom he called the “Princeton Consultants,” who helped to produce the “blue books” of intelligence analysis that the CIA sent to the White House.

Dulles often gave talks at Princeton in which he stressed the value of studying history. He discussed the craft of writing well in documents like the President’s Daily Brief. (“How do you get a policymaker’s attention?” he asked. “Just as you get the Princetonian sold. Make it readable, clear, and pertinent to daily problems.”) He noted that reading a text’s plain language is not enough to assess its meaning: For example, “many Soviet formal documents — constitutions, laws, codes, statutes, etc. — sound quite harmless, but in execution prove very different than they read.” Here, he suggested why the innovation of recruiting humanities scholars changed spycraft — and why his CIA recruited so heavily from departments of English and history. Cryptography is not the only way to make codes. Irony, implicature, politesse, euphemism, ambiguity, hyperbole, allusion, and deflection are also codes: They are ways of saying one thing and meaning another.5

These themes - understanding history and communicating clearly, even when saying one thing while meaning another - will bubble to the surface throughout Karl’s career.

Princeton’s lasting impact

As an institution, Princeton University has had a profound impact on the intelligence world.

Ultimately, the humanists who labored among stacks of books for the OSS profoundly shaped not only the course of the war, but much of note in the postwar world. Historians have called World War II “the physicists’ war,” referring to the fact that physicists worked on major research initiatives like the Manhattan Project. For similar reasons, stories of spycraft often emphasize cool toys and glamorous field operations: women firing bullets from tubes of lipstick, men planting charges to blow up trains, scientists building wonders in secret labs. Things that go boom are exciting. But the lesson that America taught the world of intelligence is that we might get a greater impact from things that rustle: monographs, photographs, newspapers, index cards. We could, with just as much justification, call World War II “the humanists’ war.”6

Like Karl, Jay was admitted to Princeton. However, he could not afford to attend, so he instead went to Washington & Lee, where he studied journalism.

The two cousins developed similar skillsets during their undergraduate days, but their post-graduation trajectories differed, driven by health and connections (both of which favored Karl).

Jay’s poor eyesight kept him out of World War II and his lack of political connections made for a long climb up the career ladder.

Karl, on the other hand, did participate in the war. And when we returned, he was immediately fast-tracked into the world of the power elite.

Not surprisingly, Princeton - and its relationships with the OSS and CIA - appears to have played an outsized role in Karl’s wartime experience, as well as his post-war pursuits.

Obituary. The New York Times, February 28, 1957.

“Patricia S. Adams Becomes Fiancee: Former Hospital Worker for Red Cross Engaged to karl G. Harr Jr., Law Student,” The New York Times, October 27, 1946.

Graham, Elyse. “The P Source: How humanities scholars changed modern spycraft”, Princeton Alumni Weekly. November 20, 2020. Accessed December 4, 2024

Karchmer, Clifford. “Princeton Pipeline”, Princeton Alumni Weekly. Accessed December 4, 2024

Graham, Elyse. “The P Source: How humanities scholars changed modern spycraft”, Princeton Alumni Weekly. November 20, 2020. Accessed December 4, 2024

Ibid.